AGTECH AND FOODTECH IN CHINA & INDIA – A TALE OF TWO COUNTRIES

This November 2011 TIME magazine cover, relays the sentiment building at the time when China was the “factory floor of the world” and the manufacturing capital, and the Made-in-China label had become affixed to everything from underpants to consumer goods. India, on the other hand, was the infotech giant, and a giant back-office for the world’s leading businesses. Also around this time, the world marked the ten year anniversary of the bursting of the dot com bubble and had begun to reinstate its trust in tech companies. On the date, the release of this edition of the TIME magazine, Amazon was valued at US$83B, today it is valued more than 10x that number. Amazon is just one such example of a company at the forefront is technology revolution we have witnessed in the last few years. The embracing and in some cases forced adoption of technology across sectors, has seen many industries being disrupted. Once unknown names have emerged as market leaders and some household name stalwarts are going bust.

This November 2011 TIME magazine cover, relays the sentiment building at the time when China was the “factory floor of the world” and the manufacturing capital, and the Made-in-China label had become affixed to everything from underpants to consumer goods. India, on the other hand, was the infotech giant, and a giant back-office for the world’s leading businesses. Also around this time, the world marked the ten year anniversary of the bursting of the dot com bubble and had begun to reinstate its trust in tech companies. On the date, the release of this edition of the TIME magazine, Amazon was valued at US$83B, today it is valued more than 10x that number. Amazon is just one such example of a company at the forefront is technology revolution we have witnessed in the last few years. The embracing and in some cases forced adoption of technology across sectors, has seen many industries being disrupted. Once unknown names have emerged as market leaders and some household name stalwarts are going bust.

Asia has its own face of leaders in tech disruption, and unsurprisingly the Big 3 are from China – Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent. These three tech conglomerates provide a distinct advantage to China, not only do they bring a wealth of data but also a sense of familiarity to investors looking to invest in the country. Their experience and data has also helped the agritech and foodtech sectors. China is the world’s largest pork consumer and Alibaba has its data and skills to develop a solution for pork traceability. Using modern machine learning and AI technologies from Alibaba, pigs can be identified by their face and vocalizations. This technology can also track all of the pigs’ activities, vital signs, and flag issues like pregnancy, sickness, or sedentariness. And it is not only these large tech companies trying to address this market, Future Food Asia Award 2017 finalist Smart AHC is also levering sensors, Internet-of-Thing (IoT) and computer vision technology to enhance the traceability of pork. China, has been luring top global AI researchers, many from Silicon Valley firms. It has built a $2 billion research park dedicated to AI in western Beijing and its spending more millions on AI research at universities and private firms. To find a tech leader from India, you would have to scroll a fair bit on over this list to see one. There is a severe dearth of data in India, which hinders research and even those who do set up AI-based ventures struggle to find the right talent and skills. Between 2014 and 2017, AI startups in India raised less than $100 million from venture capitalists. That being said several Agtech companies are leveraging what is available and even generating banks of data to help solve problems related agriculture, such as another 2017 finalist Eruvaka who is targeting the aquaculture sector by using IoT sensors.

Somewhere over the years, China surpassed India, and holds a lead that most would say is too big to catch-up to. Today there can be little comparison between China and India. While one is a booming $11.3 trillion economy, the other is just a $2.1 trillion upstart.

But how has this growth impacted the agriculture and food sectors of these two Asian giants and how does it translate to the state of affairs of the agritech and foodtech domains? In this post, we aim to provide our perspective on the how they stack up against each other, based on insights gathered all along the last years of visiting the populous metropolitans and remote rural villages in both countries.

DIGITAL PENETRATION AND R&D INVESTMENTS: THE BUILDING BLOCKS OF DISRUPTION

According to the World Factbook of the CIA in 2014, the global agricultural output was $ 4,771 billion. But a full 42 percent of this output comes from just six countries – China is the largest producer, followed by India. Needless to say that the sector is pivotal to both countries. However, moving beyond the volume produced when statisticians begin to calculate the value and the efficiency the story is a bit different.

Many residents of both countries will cite sheer size as the root cause of many of the inefficiencies plaguing the sector. There has been immense pressure on agricultural land, as demand grows and China and India contributing significantly to the 9 billion mouths to feed by 2050. Technology is one answer to help improve the efficiency of the sector. But these indigenous problems more often than not require indigenous solutions, making investment in R&D to develop new technologies and investment in infrastructure to aid the implementation of digital solutions pivotal to the cause.

Between 2013 and 2016 the percentage of adults in China using the internet rose from 55% to 71% whereas in India the number only grew from 18% to 21%. The digital divide between the two countries mirrors differences in their broader economic trajectories. This disparity in adoption rate is also the result of contrasting investment in the digital agriculture space in both countries. India has about 300-400 agripreneurs solving multiple problems in the agri supply chain but their combined revenue is less than US$100MM. Agritech has received only about 130 MM in approx. 60 early stage venture deals representing less than 1% of total VC investments in the country. On the other hand in China, Maihuolang, a platform for agriculture products that is focused on rural communities raised US$ 150M alone in their Series A round back in May 2017.

Between 2013 and 2016 the percentage of adults in China using the internet rose from 55% to 71% whereas in India the number only grew from 18% to 21%. The digital divide between the two countries mirrors differences in their broader economic trajectories. This disparity in adoption rate is also the result of contrasting investment in the digital agriculture space in both countries. India has about 300-400 agripreneurs solving multiple problems in the agri supply chain but their combined revenue is less than US$100MM. Agritech has received only about 130 MM in approx. 60 early stage venture deals representing less than 1% of total VC investments in the country. On the other hand in China, Maihuolang, a platform for agriculture products that is focused on rural communities raised US$ 150M alone in their Series A round back in May 2017.

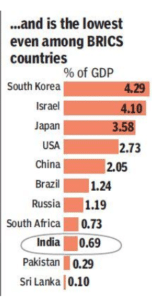

While digitization has focused on trying to reduce the inefficiencies in the value chain, hefty R&D investments are being made to improve the quality and of the output. Here the disparity is even larger between the two countries. While agri-specific figures are unavailable, China is now the 2nd largest spender in R&D after the US, accounting for 21% of the world total which is $2 trillion. It has been rising 18% a year, as compared to 4% in the US. Even more impressive is the fact that China has overtaken the US in terms of total number of science publications. Scientific papers have increased dramatically, even if their impact, as judged by citation indices, may not be that high and the US still continue to lead in terms of the number of patents and the revenue they generate. Beyond the border, India’s gross research spending tripled in the last decade, yet total R&D expenditure remains below 1 per cent of its GDP. While China is spending about US$ 400 billion India is only spending close to US$50. According to a 2017 Forbes analysis there are 26 Indian companies in the list of the top 2,500 global R&D spenders compared to 301 Chinese companies. 19 of these 26 firms are in just three sectors – pharmaceuticals, automobiles and software. India has no firms in five of the top ten R&D sectors as opposed to China that has a presence in each of them.

However even after millions of investment in R&D and digitization, investors remain cautious in both countries, since IP continues to remain a perpetual cause of concern for them. While English as a dominant language and the backbone of the Common Law helps India’s image among many foreign investors, the lack of enforceability of their laws continues to keep investors wary. While China faces similar problems of enforceability, entrepreneurs and investor alike recognize that the pace of implementation and scale up is the best barrier to entry, and in that respect China is seen as a country where the scale up potential is far higher and easier.

BANGALORE AND BEIJING ARE AT DIFFERENT STAGES OF THE AGRI FOOD VALUE-CHAIN

Over the past decade, China has witnessed phenomenal infrastructure growth. Between 2001 and 2004, investment in rural roads grew by a massive 51 percent annually. China’s leadership has charted equally ambitious plans for the future. Its goal is to bring the entire nation’s urban infrastructure up to the level of infrastructure in a middle-income country, while using increasingly efficient transport logistics and telecommunication to tie the country together. As we write China is a country where (almost) anything can be delivered within 24 hours. And specific to agriculture, China has cleared the way for private investment in large-scale farming, announcing a change in land rights that heralds a new era for agriculture in the world’s most populous nation. Envisaging a future where consolidation of land plots takes place, will help address one of the biggest pain points of agripreneurs today – reaching small holder farmers. As an example of what China is coming to call ‘corporate farming’, Kingfarm Commune platform backed by international organizations such as IFC and tech giants Alibaba and JD.com will consolidate farms to bring to life a concept of a Village CBD that will consolidate multiple land plots to unlock great productivity potential.

In India, the story is different. About 58 percent of the Indian population is dependent on agriculture and core technology is lagging in that industry. While telecommunication network has penetrated fairly deep in rural India, more basic infrastructure such as water, electricity and roads remain insufficient. However, with the country beginning to get its act together, a renewed strategy of putting rural India as the front runner could usher in a new era for the nation. But as of now potential investors in agritech start-ups see large scale implementation as a challenge agripreneurs may not be able to address to reach break even point.

These contexts pave the path for two different set of innovations. While Chinese entrepreneurs are focusing more towards improving the output and yield, many Indian entrepreneurs realize they need to first churn out more structural innovations and focus on market linkages and mechanization. To highlight this difference we can see Future Food Asia 2017 finalist Farm Friend which acts as a connection platform for farmers and drone operators. Meanwhile in India, while drones are yet to garner the trust and understanding of farmers, start-ups like 2018 applicant Distinct Horizon, are building innovative hardware to substitute hours of manual labor in rice farming for small holder Indian farmers.

These contexts pave the path for two different set of innovations. While Chinese entrepreneurs are focusing more towards improving the output and yield, many Indian entrepreneurs realize they need to first churn out more structural innovations and focus on market linkages and mechanization. To highlight this difference we can see Future Food Asia 2017 finalist Farm Friend which acts as a connection platform for farmers and drone operators. Meanwhile in India, while drones are yet to garner the trust and understanding of farmers, start-ups like 2018 applicant Distinct Horizon, are building innovative hardware to substitute hours of manual labor in rice farming for small holder Indian farmers.

This difference can also be seen in the numbers of the 2018 applicants for Future Food Asia Award. While both countries contributed similar number of total applicants – India saw 80% of applicants under Streamlining Supply Chain, Precision Agriculture and Sustainable Farming Practices categories. Some of these solutions encompassed quite nicely the Indian concept of jugaad which translates to finding a low-cost solution to any problem in an intelligent way. For example an applicant called NewLeaf Dynamics has developed an off-grid, compressor-free, renewable energy based refrigeration system called GreenCHILL which uses cow dung and agri biomass to provide safe storage and cooling of perishable agri produce. For China on the other hand single largest contribution was the category of Enhancing Nutrional Value, which focuses more around developing novel methods to process food and ingredients and improving their nutritional value and functionality, contributed 36% of Chinese applicants. This featured companies such as StartupSG grant winner, Shenzhen Xiaozao which is carrying out mass cultivation of natural microalgae and extracting derivatives such as Omega 3.

While China now begins to rival the US in agtech – and this phenomenon starts to be visible through funding trajectories that mirror (and at times surpass) those of the West – India still has to first tame its domestic challenges. If a good understanding of the overarching pain points of the F&A industries can guide VC investors toward high potential startups, risk assessment is more of a country-specific part of the due diligence. Syndicated investments help bring around the table the right expertise on critical nodes of the supply chain, and we are glad to contribute to this with the Future Food Asia platform.